TUID White Paper

Based in part on conversations with Michael Darden representing DFM Data Corp., Inc.

Tracking Transport Movements – A Familiar Example

Working in supply chain, you’ve probably experienced airline travel. When you get your itinerary, you will note the distinctive 6-character confirmation number. It ties back to a “Passenger Name Record” (PNR) that bundles personal and travel information. The PNR is created at booking and used at check-in by the passenger, shared across providers throughout, connecting itinerary management, ticketing, security, loyalty, and reservation systems.

Figure 1 – Airline PNR Confirmation Number

If your trip has several legs, a couple of airlines and maybe includes a hotel and rental car or two, each company could have its own version of the PNR. Those will quietly roll up into a background “super PNR” that describes your full itinerary. Lots of traveler conveniences result from that ID and tracking system. For those old enough to remember the before times, this replaces the fanfold of Paper-tickets and envelopes in a manilla envelope in our Day Planner.

In the aftermath of the Pandemic, stakeholders in the global supply chain scratched their heads. For decades, global supply seemed to work smoothly, getting a little better every year. Then in 2021, global logistics chaos reigned. Regional lockdowns halted production. Drivers couldn’t or wouldn’t work. Warehouses were understaffed. Large numbers of workers or their families got sick or died. COVID proved that supply chain industry operations were more fragile than had been believed, and managers had a weaker grasp of what was really happening day to day.

Mostly, the Pandemic showed that information is narrowly siloed, to the point that many parts of the industry were effectively black boxes or black holes. Over the past year or two, stakeholders in Africa, Asia, Europe, Australia, South America, and North America especially the United States, have done a deep dive into supply chain operations to understand the information transparency and communication problems. To figure out how to fix them.

Major changes are in progress in two areas:

a) laws and regulations demanding industry openness, and

b) ‘mandated’ standards to make quality data exchange possible.

Supply Chain Regulatory Push

In the US, there are two regulatory initiatives that are drawing strong industry attention as this is written. The first demands from US Congress, the Federal Maritime Commission (FMC) to improve transparency of container shipping and port operation. The second involves getting better information out of the many intermediaries (brokers, forwarders, load boards, etc.) in the domestic trucking industry under the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA).

Maritime Shipping Visibility

Bringing manufactured goods into the United States relies on shipping containers aboard specialized ships called vessels. When the vessels dock at container ports, the containers are unloaded onto trucks or trains that bring them to inland recipients. Exports happen in reverse.

In June of 2022, President Biden signed the Ocean Shipping Reform Act (OSRA) into law. The law gave the Federal Maritime Commission (FMC) new authority. Of note, Section 4 requires the establishment of a Shipping Exchange Registry, and Section 5 Prohibition on Retaliation addresses discrimination and refusal to deal. The law has provisions that will evolve over the next 3 years.

To fully address the issues, the FMC has first shouldered the challenge of managing the demurrage and detention issues that escalated during the Pandemic. Demurrage is the time a container spends waiting for a truck to pick the container up after it is unloaded from the vessel. Detention is the time that the international container spends in the US before it gets back to a port and into the hands of the ocean carrier. In other words, the FMC authority aims to improve the movements of shipping containers between vessels’ arrival and departure from US ports.

In response to the new law, on April 20, 2023, FMC Commissioner Carl Bentzel issued a set of detailed recommendations to improve data availability that would enable accurate communications. The 40+ page set of recommendations demands increased supply chain transparency at every stage of the process. The recommendations reflect the input from 18 video-recorded public hearings (collectively viewable on the FMC YouTube Channel).

A feature of the FMC recommendations is that some of the new data requirements are defined as “Open Facing”, where the data must be accessible by the public. Other data is “Closed Facing” and is only for the actual parties to the shipping transaction. At the time of this writing, the recommendations are released for public comment and the second half of 2023 will likely see an energetic, and likely heated, public discussion by interested stakeholders.

Transparency in the Domestic Trucking Industry

When domestic shippers or buyers arrange freight shipments, they have several options. Shippers can operate their own trucks or they can use intermediaries, either on long-term contract or from the spot market. Those intermediaries typically fall in two broad categories: transportation suppliers (carriers) and transportation brokers. There are many thousands of suppliers and brokers in the US and, collectively, they dictate a lot about supply chain performance.

The laws governing trucking intermediaries haven’t changed much since 1980. In US Federal Regulation, 49 U.S.C. 13102(2), defines the term ‘‘broker’’ to mean a person, other than a motor carrier or an employee or agent of a motor carrier, that as a principal or agent sells, offers for sale, negotiates for, or holds itself out by solicitation, advertisement, or otherwise as selling, providing, or arranging for, transportation by motor carrier for compensation.

49 CFR §371 governs intermediaries and it defines two intermediary actors:

- Bona Fide Agents – Persons who are part of the normal organization of a motor carrier and perform duties under the carrier’s directions pursuant to a preexisting agreement which provides for a continuing relationship, precluding the exercise of discretion on the part of the agent in allocating traffic between the carrier and others.

- Licensed Brokers – Persons who, for compensation, arranges, or offers to arrange, the transportation of property by an authorized motor carrier. Motor carriers, or persons who are employees or bona fide agents of carriers, are not brokers within the meaning of this section when they arrange or offer to arrange the transportation of shipments which they are authorized to transport and which they have accepted and legally bound themselves to transport.

Since 1980, the laws and regulations required that licensed brokers reveal aspects of their subcontracting actions and costs to the other parties to the transaction: shippers, recipients, participating carriers, and facilities. In other words, brokers have been legally obligated to be transparent about their dealings under the de-regulation law that stood for the past 45 years.

Yet, we hear everyone complain that the US trucking supply chain lacks transparency?

The reason seems to come in three parts:

- Licensed brokers often write a waiver clause into their shipping contracts that absolves the broker from having to disclose the data that the law demands. On paper, if both parties voluntarily agree to ignore the requirement, who can complain? In practice, since most brokers use the clause, customers have no operative alternative.

- A lot of new players have entered the game with novel business models. There are literally hundreds of Digital Freight Matching (DFM) “load boards” that promise to match shippers loads to capacity from valid motor carriers. To date, they have viewed themselves as more like eBay than a broker or agent. That’s their primary reason for refusing to divulge their ‘role’ in the transaction’s details and requirement for transparency to the parties.

- Finally, if found breaking the transparency law before 2018, the penalties for a broker failing to comply were nominal. Brokers who refused to disclose required transaction details were at risk of a $200 fine for the first proven refusal and $250 for each one thereafter. Shipping Exchanges, DFM providers and digital brokers weighed the low probability of enforcement of fines and chose to risk absorbing any enforcement penalties with little pressure to change business policies.

The fines for failing to respond to stakeholder requests for data in 2018 went from $200 (1st offense) and $250 (each subsequent) to $2,000 (1st offense) and a minimum of $5,000 (for each subsequent offense) liable to the company’s officer(s). Those fines far exceed the profits that brokers get on a typical load. Owners can no longer treat these fines as “cost of doing business”.

As early as 2020, Industry Associations like the Owner–Operator Independent Drivers Association (OOIDA) and Small Business in Transportation Coalition (SBTC) petitioned the FMCSA to address non-compliance of CFR 49 371.3, the transparency clause for brokers. Further, in response to the mandate in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), FMCSA acted in April 2023 acknowledging the OOIDA and SBTC petitions as valid and actionable, announcing forthcoming rulemakings.

Back in November 2022, FMCSA issued new interim guidance on how to interpret the terms “broker” and “bona fide agent”. The gist of the refined interpretation is as follows: Many load boards, digital marketplaces, and online service platforms that are currently conducting or arranging business as defined brokers should secure required licenses following Federal regulations, including maintaining transaction data for sharing with the parties.

It seems law enforcement will no longer look the other way from the industry practice of using predatory waivers and refusing to deal as retaliation. In theory, since the law and regulations have not changed, requirements could be applied and enforced retroactively. Rule changes typically grandfather in prior behaviors and apply only after the rule is formally adopted. These, however, are not rule changes, so we will have to wait and see how it is applied and enforced.

Industry Trade Associations have already begun the lobbying and legal dance. For example, SBTC filed an ethics violation for review by the Transportation Intermediaries Association (TIA) as one of its largest member brokers still has the waiver in their shipper contracts. This and other Anti-Fraud related PR work will play out in Washington and in the courts over the coming months.

A Practical Obstacle

If the perceived lack of supply chain transparency were due mainly to industry intransigence, strong regulatory initiatives might clear up the problems. However, the example of the airlines’ PNR system highlights a practical reason why, even with the best will in the world, the goods supply chain probably can’t fully comply.

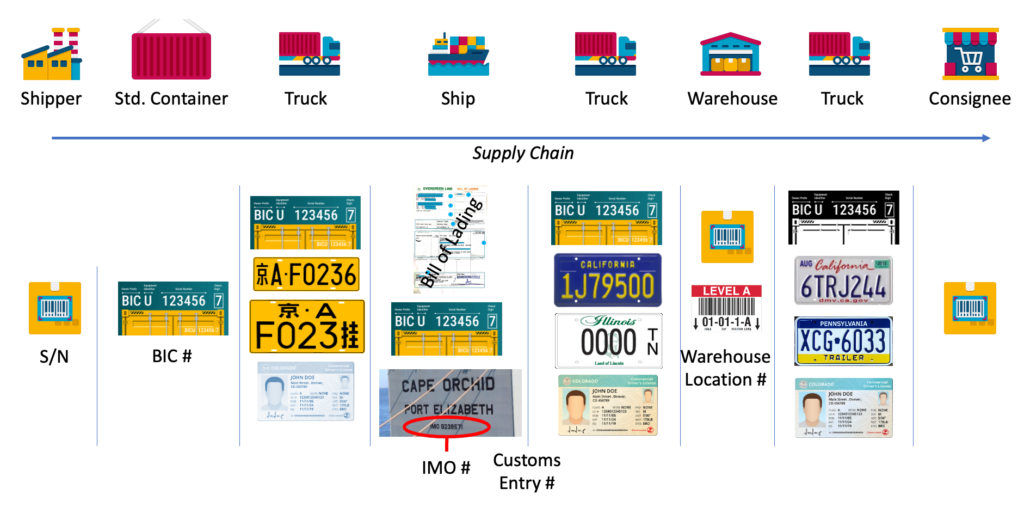

As illustrated in Figure 2, virtually everything in the supply chain system has a unique identifier: trucks, truck trailers, rail cars, and often even many pallets and boxes. Plus, there are lots more paperwork IDs like “bill of lading number” that are unique within a given shipping context. We are not short of things to record and track. The difficulty is that each broker, carrier, warehouse, port, shipping line and web service resides in (and protects) its own data silo. How can we know which shipping records connect to which other ones across company boundaries? How can we be sure that shipments are not double counted, or missed altogether?

Figure 2 – Competing IDs in Supply Chain

It may be possible to follow the breadcrumbs manually. To see an entire journey, an interested party can piece together fuzzy documentation and variously labeled items from multiple industry players. That can work in specific cases, but it is not suitable for automation across large numbers of shipments, let alone a whole industry. Effective automation requires a systematic record-keeping system like the airline PNRs and super PNRs.

The situation is surprising when you think of the operational and data standards that have been imposed on and adopted by supply chain operations. Some of these (e.g., ISO 9000, ISO 27000, and ISO 28000) are global in scope and acceptance. They demand that companies install systems to keep track of pretty much everything related to their concerns (quality, security, etc.). Surely one or more of these would have addressed the problem. However, the recent hearings, studies and analyses all agree that the disconnects remain.

Enter Standards: the ISO 8000-119 TUID Example

The Working Group (TC 184 / SC 4) associated with the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) is working on a standard (ISO 8000-119) for a TUID, Transport Unit Identifier. The group is supported by another major standards body, ASTM Committee F49 on Digital Information in the Supply Chain. Support from two standards development heavyweights aligns the TUID concept with existing standards and lends serious gravitas and credibility.

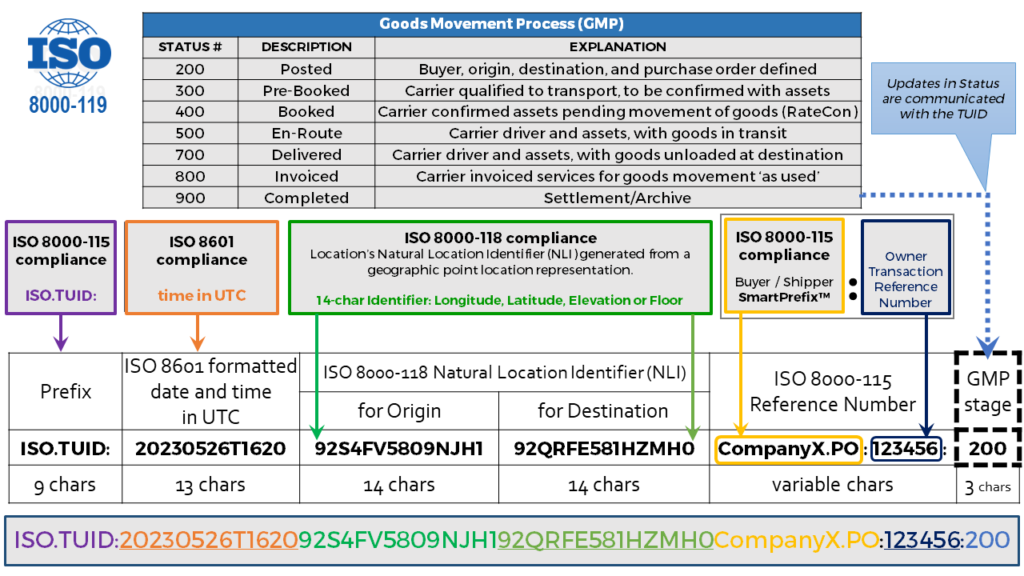

The concept for the TUID is to build a globally unique identifier that follows a ‘load’ from birth to death… built by combining previously standardized data elements as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 – Construction of ISO 8000-119 TUID (Working Draft).

The constituent parts are as follows:

- The ISO.TUID: prefix – designation to signal construction, what this prefix represents. (ISO 8000-115 Data quality: Syntactic, semantic and resolution requirements)

- The date and time that the load is available (accurate to the second, adjusted for time zone) (ISO 8601 Date and time — Representations for information interchange)

- Standardized encodings of the latitude, longitude, and floor for both the origin and destination. (ISO 8000-118 Data quality: Natural Location Identifiers)

- A standardized identifier for the legal organization that is initiating the shipment, traceable back to the legal jurisdiction that records the authority of the organization’s existence. In Figure 3, this identifier is a the SmartPrefix™ that is available from the non-profit organization Electronic Commerce Code Management Association (ECCMA). The SmartPrefix™ is the ISO 8000-115, custom human-readable derivative of the ISO 8000-116 Data quality: Authoritative Legal Entity Identifier.

- An internal code that the source organization assigns to distinguish this shipment from others it may send. It is up to the source organization to guarantee the uniqueness of this code. For example, it may be an internal accounting designation that conveniently fills the purpose (e.g. PO (purchase order), SO (sales order), BOL (bill of lading), …).

In addition to the TUID proper, the standard defines a set of Goods Movement Process (GMP) status codes that are appended to the TUID to signal major milestones in the shipment’s progress towards its destination. These are not part of the actual identifier but they are defined as modifiers that can be updated as the shipment progresses along its journey.

To be clear, at time of writing, the TUID Standard Working Draft (WD) in Figure 3 is still under active development and discussion. Comments and inputs are actively encouraged. Industry participants will be able to rely on it commercially after it has been discussed, refined, voted on, and published in the ISO catalog. Nonetheless, Figure 3 shows the direction that work is heading and that makes it possible to speculate and preview how a TUID-based system might operate.

A Strategy Global TUID Application

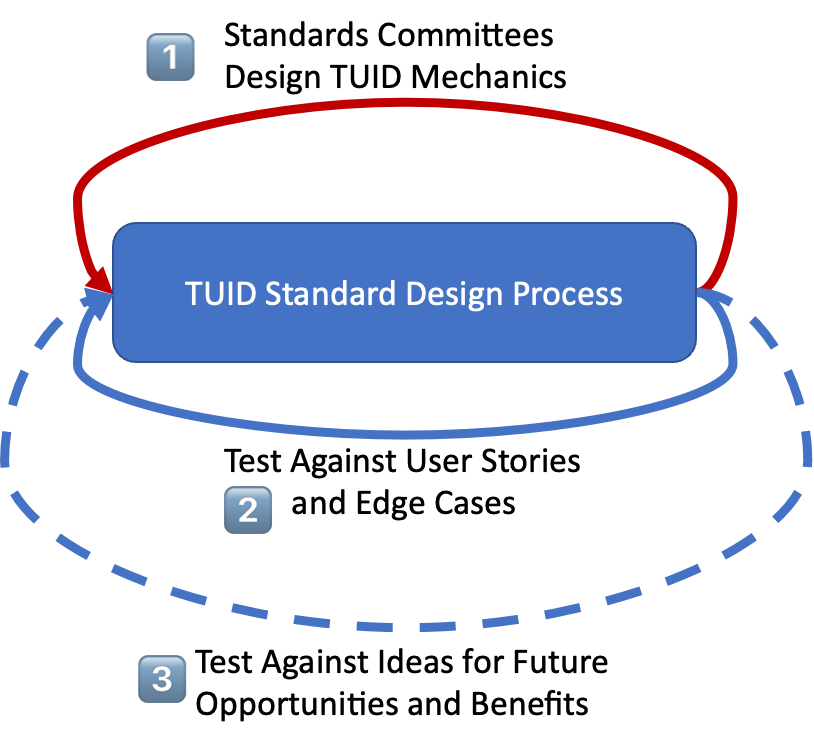

If the TUID concept seems intriguing, there is justification to follow a design process like the one shown in Figure 4. The work would proceed in three looping flows:

- Design and test potential TUID mechanisms (e.g., fields to include, hashing, data structures).

- Take each iteration of the TUID mechanical design for test drives against a library of user stories and edge cases. The goal is to understand in advance how it might be implemented across industries. Meanwhile, actively search and solicit more cases for inclusion in the library.

- Repeat the process against a library of ideas for future uses and benefits of the system. Imagine new things that might be possible with the TUID and use those industry driven ideas as test cases for the design plan of the future state of the international standard.

The process of designing and exploiting a TUID will require a process like the one in Figure 4. The sooner the industry begins to pursue it in appropriate Standards Development Organizations, the sooner existing problems can be solved, and future opportunities prioritized.

Figure 4 – TUID Standard Design Process

Phase 1 – Design the TUID Mechanics

There are a lot of areas and opportunities to brainstorm and design how the TUID system would be structured and function in standard practice. The following sections outline some concerns, opportunities and possibilities for input and consideration. This is far from a comprehensive list, but it should be enough to seed thought and input from interested stakeholders.

The TUID can be self-generated

The structure in Figure 3 can be assembled by anyone at any time. You don’t need big brother to kindly dole out a TUID. You can build as many as you like, whenever you like. The only parts that require formal external input are the legal identifiers (SmartPrefix™ or ALEI) and they only need to be generated once for each originating organization (alternate IDs, i.e. DUNS, GLEIF LEI, GS1 GLN, etc.). Unless the shipper is bought, sold, merged or divested, those parts don’t change. A shipper can reuse their SmartPrefix™ in an unlimited number of TUIDs at no marginal cost. Since the original ALEIs and SmartPrefix™ are pretty cheap, small shippers are easily included.

There is only one TUID per shipment / load

The airline PNR system allows participants to use their own PNR systems and roll data up into a combined Master PNR record. The idea behind the ISO 8000-119 TUID is to create a single, unique identifier that travels the full length of the shipments’ journey. The shipper generates a new TUID for every shipment and everyone who discusses, handles or settles the goods must ask for the TUID, offer the TUID to the next handler, and demand the TUID if it is not offered automatically.

It’s reasonable to ask: “why not use the PNR approach?” After review, it seems like that would create problems given the different structures of the two transport industries. The passenger travel industry has fewer carriers, and most are relatively large companies. They have organized in co-opetition to collaborate around a PNR approach with government oversight within Federal Safety Requirements. This was done more easily with fixed airports, as opposed to that of an industry like supply chain which has hundreds of thousands of carriers and countless millions of related shippers and customers around the world. For this use case, passing along the standard TUID is a lot easier.

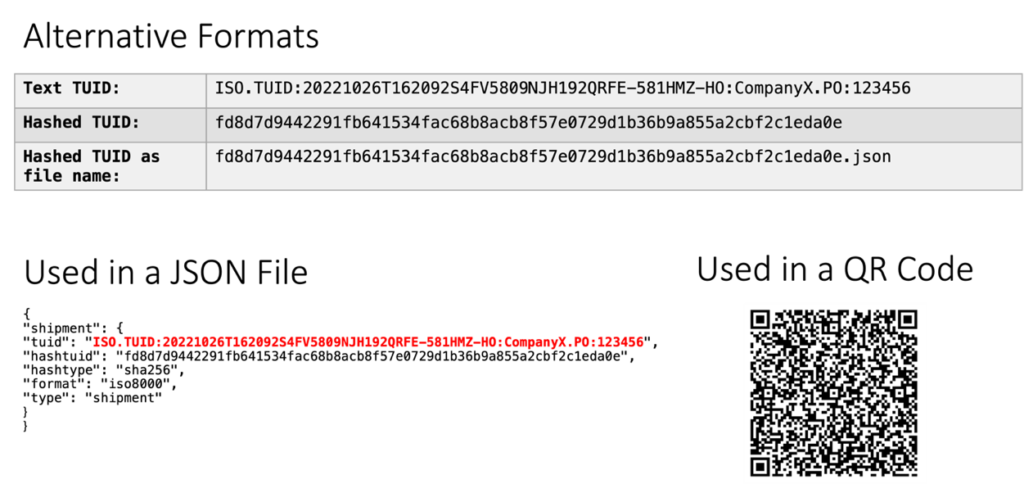

Format, Privacy and Validation

The format in Figure 3 is human readable. If that is a concern, many of its benefits can be harvested in ways that are more anonymous. For example, one could apply a standard (e.g., SHA-256) hash code to the text TUID and send that through to the intermediaries. It would be unique and the meager shipment details in the text TUID would be obscured. Presumably, the ultimate recipient would be sent a copy of the hashed TUID for load validation, or possibly sent the text TUID along with instructions to apply the correct hashing algorithm in order to reveal the human readable TUID data.

Figure 5 – TUID Formats

As shown in Figure 5, the text or hashed TUID is concise enough that it could be used as a filename for data packages (e.g., JSON) that contain additional details. It can be incorporated into data files that are transmitted with the shipment and the text or hashed TUID could even be encoded into a QR Code or RFID tag that is applied as a label to the shipped items.

The TUID needs to start at the Beginning

Perhaps the most fundamental application aspect of the TUID is the importance of applying it as early as possible in the shipment cycle. Figure 6 shows a common situation where a shipper accepts bids from several carriers. Each participant has a rough idea about the proposed load, but there is not yet a definitive shipment designation that means the same thing to everyone.

Figure 6 – Suppliers Flying Blind

It is not uncommon for a shipper to advertise a shipment to carriers (especially in the spot market) and then re-advertise it if the shipper is dissatisfied with the first round of transportation service offers. The shipper may be clear about which shipments are the latest version, but the transport suppliers they have previously dealt with may be understandably confused.

The problem is that, while there are lots of ways systems identify goods movements (shipper IDs, container IDs, truck license plates, etc.), these are usually created or associated after the shipment has been readied for transport and has already been booked with a carrier.

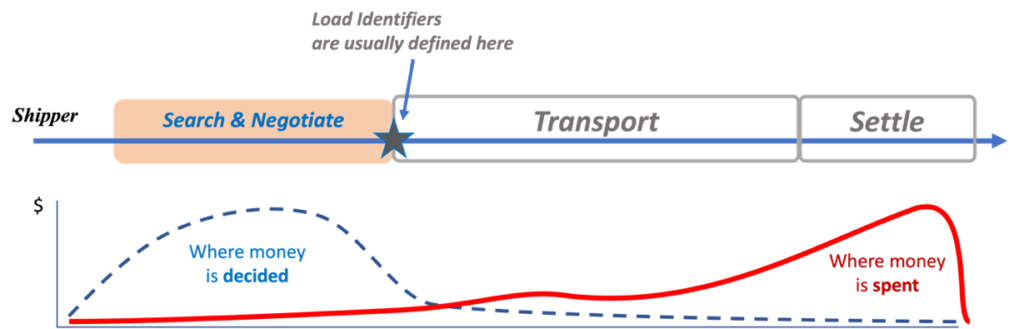

That event typically occurs when the load is dispatched, which is often well after the time when the shipper and prospective suppliers do the searching, selecting and negotiating to find the needed containers, ports, vessels, carriers, etc., creating the situation shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7 – Supply Chain Decisions vs Expenditures

In logistics, the bulk of the money for the service will be expended after the services have been delivered. However, the planning and deciding that dictates the size of the checks happens during the search, selection and negotiation phases. Potential carriers may risk repositioning assets in the hope of work. If there are multiple load postings, many carriers and intermediaries may be working to secure a given load, and if they are not notified, they may continue pursuing it after the load has already been booked with someone else. No one knows exactly how much wasted effort and misallocation of resources is caused by these avoidable uncertainties, but whatever the number, the supply chain system runs considerably less efficiently because of it.

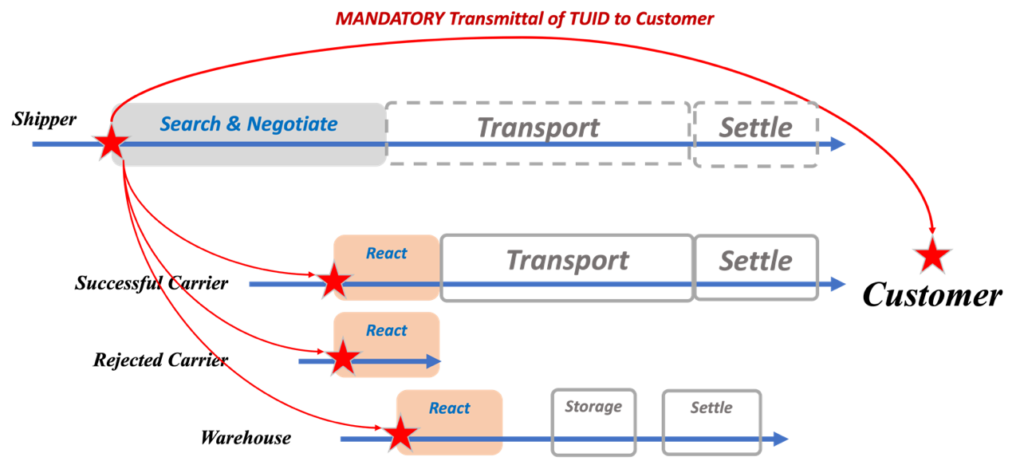

If a standard TUID is uniformly generated before the shipper begins to search and negotiate with suppliers, it could simplify and clarify communication for everyone. As shown in Figure 8, every potential business partner would know which shipment / load they were dealing. If a shipper wanted to update the load characteristics or re-issue the load solicitation after Booked, the fact that the TUID remained the same would signal to everyone that this was not a new or additional load.

Each TUID Shared as Shipment Confirmation for the Ultimate Recipient

Another concern is that the shipper might issue multiple TUIDs for the same intended shipment, either to fool suppliers or out of laziness. TUIDs are, after all, nearly free. One way to limit this sort of abuse is to require that the shipper notify the ultimate recipient whenever a TUID is generated. It is assumed that most shippers won’t want to spam their customers with spurious IDs.

Figure 8 – Protecting TUID Validity

If the transport system shown in Figure 8 is universally adopted, every shipment would be uniquely identified to every participant, even the ones who unsuccessfully seek the load or only consider and estimate the feasibility of offering to take the load. If a carrier, saw a later notification with the same TUID, they would know that it was the same load, not a new opportunity.

TUIDs never die – they just get saved for posterity

Since the TUID is globally unique for all time, there is no reason to delete or recycle it. When a shipment has been completed and settled, the TUID can safely remain as a label in the databases of each company that considered or handled it. Properly constructed TUIDs will never be confused with any other.

Keep the TUID Separate from the Shipment’s Meta Data

The TUID is just a naturally occurring label for a shipment / load. Every shipment will have a lot of other data associated with it. That data may also change or vary as it makes its journey. In most cases, the other critical information will reside in the transaction and master data of the organizations that handle it on the way. Organizing that quality portable data is the broader goal of the ISO 8000 family of standards. However, the TUID needs to be simple and totally independent from the other descriptive information. If a shipper decides to add another pallet to its planned shipment, that information should be updated in the status change and data bundle that is keyed to the TUID. If a carrier wants to add an event record (e.g., breakdown and delay), that should be appended as a note with status update. Regardless, the TUID stays the same throughout.

A Global TUID System Mandate

Given the profound impact of globalization and the global supply chain, any TUID system will ultimately need to become a global standard. It won’t be sufficient or practical to apply the TUID in a single jurisdiction.

The US might adopt a standard TUID for its domestic shipments and, perhaps, shipments that are imported or exported from the country. However, the North American logistics system also includes shipments between Canada and Mexico. Some of these may compete for US trucks and warehouse space. Should they be ignored? Wouldn’t it be better if all three North American countries adopted a harmonized standard TUID?

Expand this thought to include Latin America, South America, and then apply the concept to Europe or Southeast Asia. The simplest solution is to create a TUID system that is built from the start around an international standard and then encourage everyone to embrace and adopt it.

In the MTDS April 2023 report, Commissioner Bentzel stated:

“In large part, stakeholders are already in agreement on these [real-time information and harmonizing content] recommendations, what needs to happen is to put the recommendations into practice.”

As the world’s largest export/import economy, the US, led by Homeland Security, Customs and Border Patrol and the Federal Maritime Commission, is in a strong position to demand that shipments in and out of the US be made AVAILABLE using the standard TUID. If logistics organizations around the world were incented to adopt the TUID for all US, European, global shipments, they would quickly find it easier to calculate the TUID across all their shipments.

Even more important is the need to avoid dueling systems. It would be tragic if Europe and the US adopted separate TUID systems that were incompatible. It would also be unfortunate if one jurisdiction adopted a standard, then had to wait as other jurisdictions invented their own, followed by a wasteful exercise in harmonizing the different systems.

The TUID is available to support this digital transformation. Incubated and set for hardening in the recognized Standards Development Organizations (SDOs), ISO for the 8000-119 TUID format and GMP Milestone Steps, ASTM F49 for the inclusion, collection, coordination, and alignment of existing standards work from UN/CEFACT, ICC, GS1, and DCSA, and creation of gap-filling and supplemental standards, and others in the private sector. On June 9, 2023, ASTM F49 proposed its Draft Call-to-Action for ASTM standards on container availability that would build on complementary work from UN/CEFACT and GS1.

Phase 2 – TUID Implementation

If the TUID system is complicated or expensive, it will be one more thing on the shipper’s plate and there is likely to be resistance to adopting it. Hence, the goal is to create a system for TUID generation, that is easy to use in at least the following ways: it’s free, has infinite capacity, it’s easily automated, and it’s disposable. The easiest way to achieve this is to implement a TUID generation system that is linked to the software that shippers and carriers use currently to produce their goods and manage their shipments. The following scenarios would check those boxes.

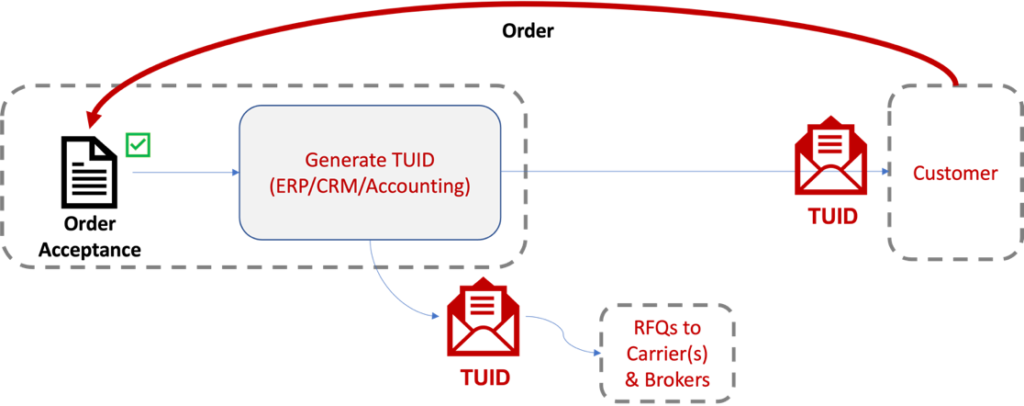

A) Response to an Order

Figure 9 shows a system where the act of order acceptance triggers the generation of the TUID as a key byproduct. The TUID is automatically transmitted to the customer and is automatically added to the electronic communications for potential transport suppliers.

Figure 9 – Issuing TUID in Response to an Order

Even if there are changes to the order, the “shipment ID” will persist as an organizing concept. If the order were cancelled, the TUID would be archived and everyone who had been informed could be notified.

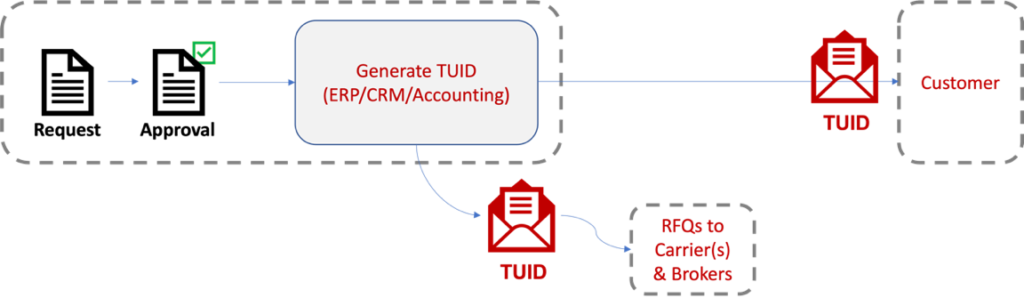

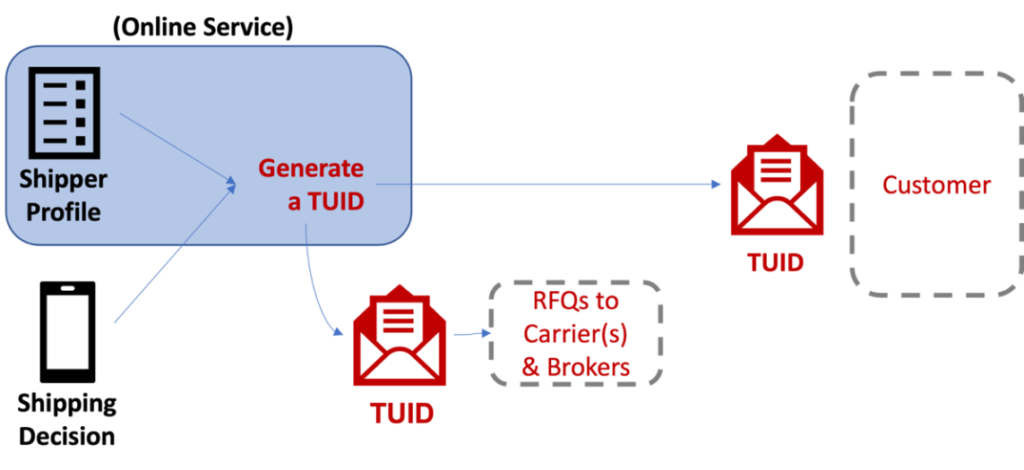

B) Decision to Ship

When a shipment is not a response to an order, a plausible decision point for creating a TUID would mimic creating a purchase order. In most enterprise software systems (ERP, CRM, accounting), employees submit a “purchase order requisition” for approval. Once it is approved, the system generates a purchase order which can be sent to the prospective supplier. It would make sense to institute a “shipment request” action and add it to the enterprise software. As soon as the action is approved, a standard TUID would be generated, recorded and transmitted to the ultimate shipment recipient as well as prospective logistics suppliers. A system configured like the one in Figure 10 should be easy to implement in most enterprise software.

Figure 10 – TUID Creation Process

In real-world situations, the process shown above will align closely with the PO requisition process and, depending on how an organization sets up its IT system, the TUID generation might be a minor extension (e.g., checkbox) or special case of the PO process.

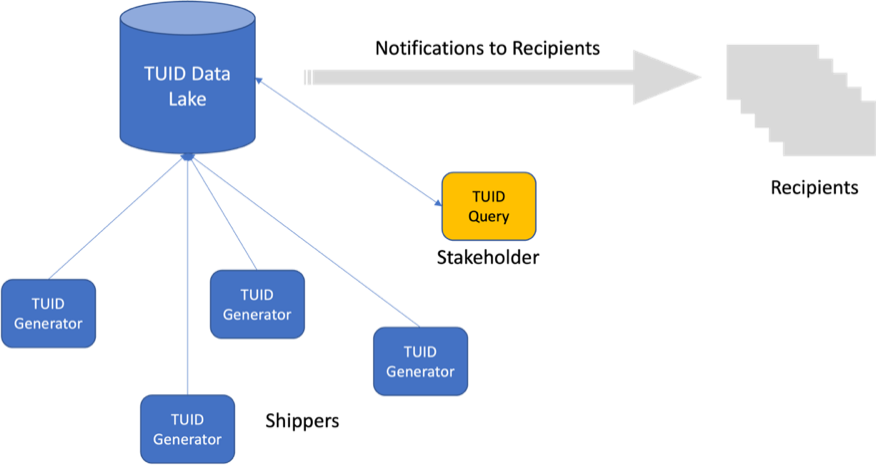

C) Third Party TUID Service

Many shippers and logistics customers are small-scale or occasional users. They may not have a sophisticated ERP or CRM system or they may only book shipments a few times a year. For these participants, it would be nice to have an online service to manage their TUID needs.

Figure 11 – Requesting a TUID from a Service

In Figure 11, a subscriber would use an app on their phone or in a web browser to set up an account with the online service. When they fill out their profile, they would submit or generate their legal identifier (e.g., ALEI and SmartPrefix™) and shipping location. Subsequently, each time they generated a shipment and load, they would enter the destination location and email. The service would return a valid TUID and would email it to the ultimate intended recipient. The system would retain a record of shipments for accounting, backup and tracing purposes.

User Stories and Edge Cases

Once the basic concept of a global standard TUID is accepted, there are lots of technical details to work out concerning how it will be implemented and/or affect operations. To answer these questions, the TUID standard design process should assemble a library of user stories and edge cases. When the proposed standard design can account for the situations in the library, we will know we are getting close to a practical industry solution.

A thorough set of user cases will probably number 75 to 100 examples … possibly more. The following examples illustrate the type of story that would be helpful in focusing design thinking.

Using a 3PL or 4PL

Many manufacturers rely on the services of a 3PL or 4PL logistics service. In these cases, the service provider assumes responsibility on a turnkey basis. For example, a manufacturer may hand over responsibility for outbound logistics at the point its goods come off the manufacturing line. The logistics service may even embed a staff member in the factory to oversee everything that happens after that. In this case, the manufacturer and the logistics service would decide where and how to generate the TUID. Two options spring to mind:

- The manufacturer’s CRM system could generate a TUID when the customer order is accepted. This is copied immediately to the logistics service.

- The logistic service could generate the TUID under its own name when it takes control of the order for processing. The TUID would be back-copied immediately to the manufacturers CRM system.

Either of these methods would create and implement the TUID at an appropriately early point in the logistics cycle. It would probably be just a matter of convenience which one is chosen by the two parties.

Customer-Directed Pickup

A recycling company drops an empty trailer at a manufacturing plant to pick up scrap. When the trailer is full, the facility calls the recycler to pick it up. The recycler sends a truck and swaps an empty trailer for the full one. In this case, the recycler is responsible for hiring the truck, driver and allocating the trailer, so they should probably generate the TUID. It would be a matter of preference whether they assigned the TUID when the empty trailer is dropped off or the full trailer is picked up.

Convenient Shorthand for Banks and Factors

A Factor gets a payment request from a carrier with list of TUIDs and recipients. The Factor eventually sends each recipient a list of relevant TUIDs and asks for the status. The recipient’s email could respond as follows:

[ISO.TUID: [time][origin][dest][Co.PO:ID]:810[time][party]] – Invoiced

[ISO.TUID: [time][origin][dest][Co.PO:ID]:214[time][loc][party]] – late; not yet received.

[ISO.TUID: [time][origin][dest][Co.PO:ID]:856[time][party]] – Ship Notice

[ISO.TUID: [time][origin][dest][Co.PO:ID]:990[time][party]] – Cancelled

The communications are short and sweet, but they clearly tell the Factor how to direct their attention and efforts. Presumably, the second TUID response would trigger an immediate red flag. A system like this might notably reduce the Factor’s auditing costs.

Cleaning Phantom Data

A shipper posts a load on A LOT of load boards and broker sites. When the load is covered (booked), the shipper is lazy about removing the now-invalid postings. The load boards (or DFM services) can’t clean up stale data because they can’t tell if a listing on a different site is really different or just a repeat of the same (now taken) load on their site. If every load were posted with its TUID, it would at least be possible to make and use utility systems to clean up the mess.

Consolidating Data on Multipart Shipments

A European equipment company sells a big system to an American factory. The heavy equipment needs lowboys and special handling. The bits and pieces are stuffed in several containers. However, it is logically all one shipment and every part is needed for the equipment to work. If all paperwork (electronic and otherwise) listed one master shipment TUID, it’s possible that some costly mishaps might be avoided.

Phase 3 – Imagine New Opportunities for Industry

Everything discussed to this point perceives the lack of a TUID as a serious weakness that needs to be fixed. The TUID WD standard offers a remedy, but it is not yet perceived as a new benefit. Let’s change the perspective and ask what the TUID can do to create new features or capabilities or value-added for logistics firms, the supply chain industry, and policy makers.

As the new standard is being conceived, we should also try to imagine futures where a TUID system does things we can’t do now. The process will resemble the search for user stories and edge cases, but with a wider and more imaginative perspective. Below are two examples of the type of imagination that might be useful.

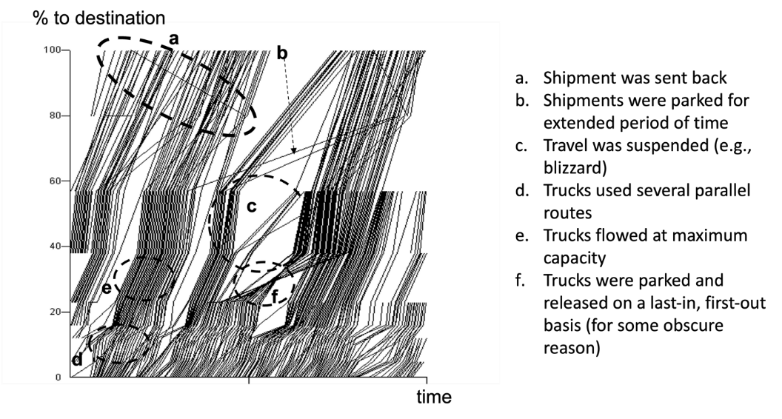

The ISO 8000-119 TUID WD contains several pieces of operational data. Collectively, they would allow the supply chain industry to create more detailed, large-scale maps of shipping movements. Figure 12 shows an example of a “distance-time diagram” for flows of goods.

Mapping Shipment Flows

Imagine that one could spontaneously generate a comparable diagram for any origin-destination pair and have it be accurate down to the minute. Would that be valuable to shippers, intermediaries, city planners, law enforcement, policy makers, etc.?

Figure 12 – Distance/Time Diagram

Shipment Validation

Suppose every time an industry participant generated a TUID, it uploaded a copy to a centralized data lake (possibly at a qualified Industry Association). Optionally, the data lake might handle the task of informing the ultimate intended recipient. This is sketched in Figure 13.

Figure 13 – Shipment Validation

To address industry-wide fraudulent behavior, stakeholders in the industry could perform a validation check against a TUID (or perhaps against a hashed TUID) that any stakeholder had concerns about. That would tell the stakeholder that the shipper had a valid TUID (and hence was known to have an identity that has been validated and certified by a legal authority).

Fraud resistant activities could be extended much further if the TUID generator were required (or allowed) to upload supporting meta-information about the load.

The concept of shipment and load validation can be taken as far as regulations, standards bodies, and industry stakeholders’ desire.

Adoption of the internationally based TUID system will make many such system services possible. Without a unifying TUID system, those ideas will be difficult or impossible to achieve.

Conclusion: A Strategy for Building Industry Acceptance.

It is one thing to design a data mechanism. It is another whole level of hard to convince an industry to adopt it as a standard. I have some specific ideas on how that might be done that are partly derived from the use cases and future systems listed previously.

The Cliffs Notes version is that this likely cannot happen solely by government or big company dictate. A mandate will work initially somewhat, but resistance may build before it reaches critical mass.

The way this type of standard has spread in the past (e.g., in the early days of ISO 9000) is with “stakeholder pull”.

- Shipping Exchanges may require their customers to provide a TUID to broker their Order, enabling them to communicate digitally with competitors when shipment have been confirmed Booked, reducing the spent efforts of chasing phantom loads.

- Banks and Factors may decide it would be handy to know from the ID where it started and what the shipment and load journey progressed through and when. They might ask for it and be more cooperative when shippers or carriers supplied the TUID.

- Big customers might assign slots on their shipping dock a bit faster for carriers supporting unifying TUIDs in their paperwork.

- Customs and Border Patrol might expedite container clearance if a TUID were present.

Eventually, it would be easier to create the naturally occurring TUID for every shipment than to try to keep track of who required it and who didn’t. Getting this buy in could start simply:

- Publish an authoritative (e.g., ISO) standard for a TUID that is fast, cheap, and easy to generate. That is already in progress, and you can join this work: https://dfmdata.com/join

- Begin a dialog with a few big, influential stakeholders (shippers, trucking firms, brokers, customs, banks, factors, regulatory agencies, customers, etc.) and convince them that they would benefit if their business partners routinely supplied, used and requested TUIDs. Evangelize the relevant use cases and then let them ask their logistics vendors to participate in spreading the best practice of the TUID System.

- Begin a dialog with software and systems services vendors to add automated TUID generation and handling to their offerings. Plant the innovation seed that they could then look for ways to leverage in their prospective innovations.

It doesn’t seem impossible to me. I think it is inevitable. I predict that within the next few years, there will be a globally accepted TUID System to communicate data flawlessly about assets and services that are deployed to move goods around the world. Mark my words!

Retired emeritus professor of Supply Chain Management from Auburn University. Dr Uzumeri earned his PhD. from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in 1991. Dr. Uzumeri has many academic papers published on ISO 9000 principles, Industrial Systems and Global Standards.

Download the TUID Whitepaper: Rationale and Plan for a Standardized Supply Chain Transport Unit Identifier (2023-06-12)

Download the second DFMDC Whitepaper: Request for Comment: Draft Method for a Transport Unit IDentifier (TUID) (2021-07-22)

Download the first DFMDC Whitepaper: Driving Collaboration Between Digital Freight Matching Providers (2021-02-24)